What is a Lumber Trader?

Matt Meyers

- Thinking

- February 27, 2023

What is a lumber trader?

It’s a simple question with a simple answer: A lumber trader buys and sells lumber for profit.

Why don’t lumber producers and lumber buyers just cut them out? After all, nobody likes the middleman. Understanding why they exist helps you understand their significance in the supply chain, and why Yesler is investing in tools that help traders win more trades.

Why does the industry need lumber traders?

Lumber traders operate within the wholesale layer of the supply chain. They don’t own production assets, nor do they typically fulfill last-mile demand to home builders. You can’t walk into their operation and buy lumber off a shelf. If you walk into a lumber trader’s office, you’ll see people, computers, phones, and whiteboards, but not a stick of lumber. They are the middleman. And everybody tries to cut out the middleman.

“Buy factory-direct” is a phrase that resonates with buyers of groceries, mattresses and lumber. In other words, “cut out middlemen” profiting from parasitic interference in a free-flowing liquid market.

What if the wholesale lumber trader, the unjustly maligned middleman, is a critical link in a functioning lumber supply chain?

In lumber, wholesale traders create value for buyers and sellers. Otherwise, they wouldn’t exist. They book freight on lumber loads. They issue credit on terms often more generous or flexible than producer terms. They solve short-term supply and demand problems for buyers and sellers building strong, old-fashioned relationships of trust. But these are the features that differentiate wholesale traders, not the reason for the existence of wholesale trading. The reason wholesale lumber trading exists as a profession, and will continue to exist in the future lumber supply chain, is because they are fundamental to the market: Lumber traders create liquidity.

To understand the critical role of wholesale lumber traders, you first need to understand the fundamental problems at play on both sides of the market.

Demand side problem

Demand is volatile on three dimensions simultaneously. First, it is cyclical and not recession-proof. Second, it is seasonal. Third, the daily lumber needed at construction sites is unpredictable and varies in volume, species, grade, dimension, and length.

Supply side problem

Mills are built to run. They are either on, or off, but not typically in between. Why? Because skilled people operate them. Mills can run different shifts, but they can’t change their shift posture every day for variable demand or they’ll lose their skilled people to other employers.

When something goes wrong at a mill – fire, breakdown, etc – the mill goes from on to off. The mill is highly motivated to go back on, because logs are still stacking-up, people are standing around, and the high-cost asset is not producing.

When the mill is on, it produces a relatively steady output, measured in board feet. That’s a volumetric measure that discloses nothing about what lumber products they produce. And the what, can vary. A mill might produce 200 million board feet of lumber annually, but on any given week they are producing a completely different lumber product or species than the week prior.

Why? Because lumber is a breakdown technology. The logs coming in the door today dictate the lumber going out the door tomorrow. Today’s log input may be 13 inch diameter straight logs, whereas tomorrow’s may be 11 inch diameter logs curved like bananas. The mill will produce roughly the same total board footage (volume), but the dimensions, lengths, and grade of finished lumber will vary.

The disconnect between the Demand side and Supply side creates the need for lumber traders!

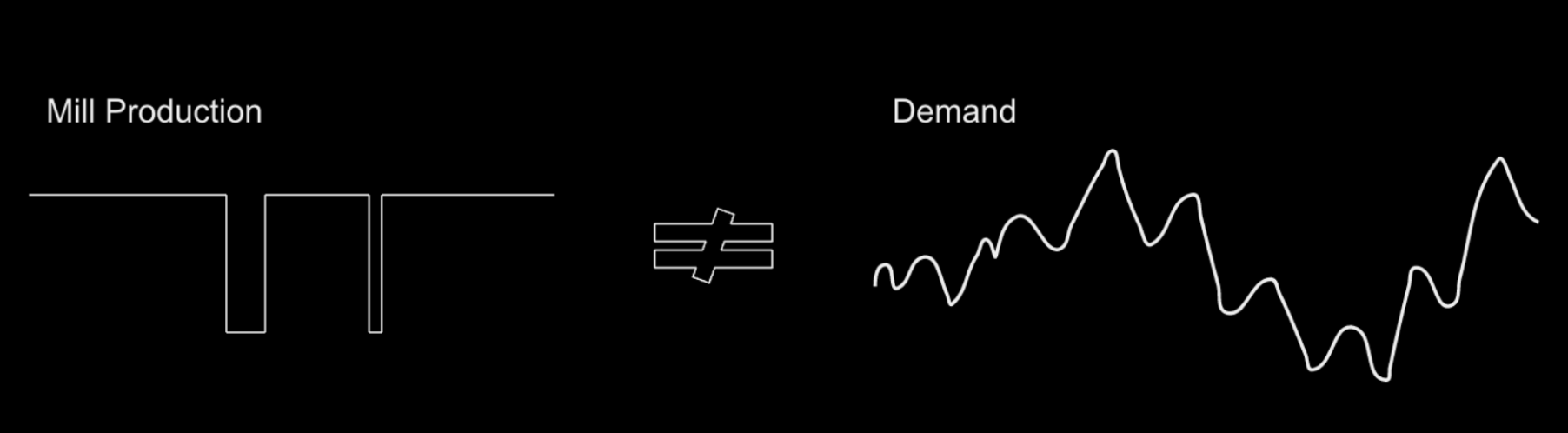

Mill production volume on any given day, week, or year does not equal the demand.

Enter, the unjustly maligned middleman – the wholesale lumber trader. The fundamental reason for their existence is to bridge the inequality between production and demand, every day. They are risk takers, hedgers, betters, and relationship builders that keep the market liquid.

Who is a Lumber Trader?

A lot of people call themselves traders. Traders come in many forms and collectively, they create liquidity amidst the inequality of supply and demand. But how they do that and their importance to the overall supply chain varies.

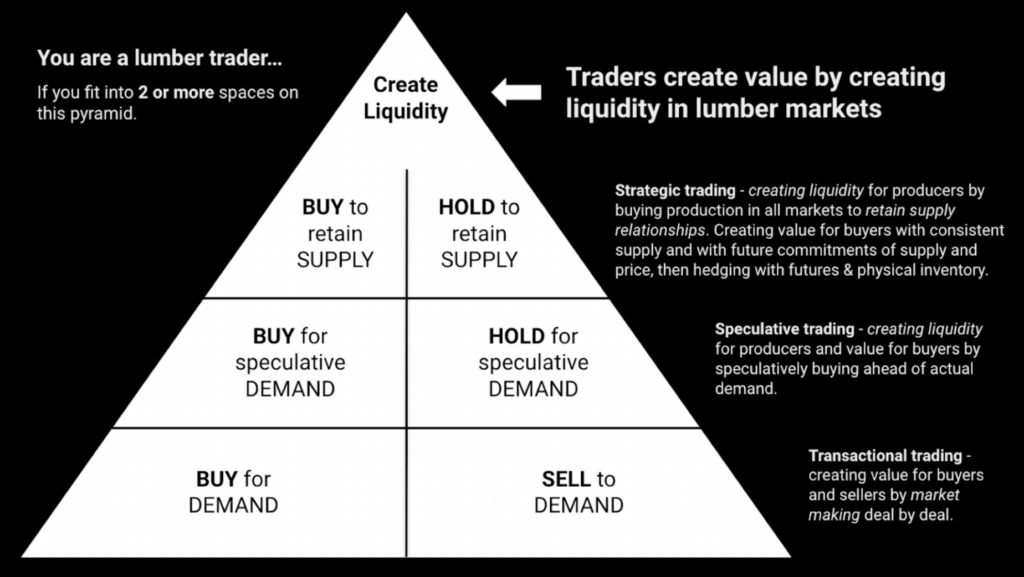

The different roles can be represented as components of a pyramid building up to the ultimate collective function of liquidity creation. If a person performs two or more of the roles identified on the pyramid below, they can call themselves a trader. The risk taken and value created both increase toward the top of the pyramid. Greater risk = greater reward (and greater cost of failure).

At the base are traders who buy and sell transactionally. They buy and sell in one day, but only with a purchase order in hand from their customer. The term “transactional” is not dismissive or demeaning. These traders act as an extension of either the sell side, the buy side, or both simultaneously and can add value to both in the process. Some producers outsource their selling, some buyers outsource their buying, and lumber traders are the value creators and beneficiaries.

On the next level are speculative traders. They buy one day, to sell the same day or very soon thereafter (ideally before the product leaves the mill). They speculate, but they don’t take large positions. Sometimes they speculate by buying one product (2x4x8’) and turning it into another (2x4x92-⅝) at a secondary processing operation. They create value like transactional traders, plus add value for mills by committing to loads ahead of demand or meeting unique customer needs.

The top level is strategic trading. They perform the same roles as the bottom layers in the pyramid, plus they take positions as required today to retain long-term supply relationships for tomorrow, and sometimes commit volumes and prices to their buyers at future dates, occasionally using futures markets along with physical lumber to hedge. Most importantly, they commit to loads from mills every day, regardless of market conditions. This consistent takeaway, sometimes sold at a future loss (or big profit)l, makes them indispensable to the suppliers and ensures them future access to supply. This, in turn, makes them indispensable to their buyers because they always have supply. Highest risk, highest value, highest reward.

Will technology change the structural inequality between supply and demand? No, but technology can help traders who make their living bridging this inequality compete and win more trades!

The role of technology

Technology’s role is simple – to power the traders who create liquidity. A trader is more valuable to the supply side the more volume they can move. Similarly, a trader is more valuable to the buy side the more supply options they make available to the buyer. Technology can power both the supply and demand side for the trader to create liquidity in a functioning market. The trader makes more money because they trade more loads. Yesler’s mission for traders is simple: to help traders win more trades.

Traders are not middlemen parasitically extorting value from the supply chain, but instead, they create liquidity in lumber markets. Technology will transform the trade, but the risk-taking traders who create value will continue to play a major role in the future of digital trading, powered by Yesler.